What is the “Sound” of Duluth?

What is the sound of Duluth? Or Minneapolis, Brooklyn, or Austin, TX for that matter? Looking at the last two cities, you might argue that a jangly variant of lo-fi garage pop epitomizes their current “sound.” But characterizations like that don’t really get at a city’s sound so much as the type of music that’s popular among musicians from that locale. And thanks to the proliferation of Internet music culture, chances are the aesthetic popular in one larger city is also popular in another. (Do you see how I just conflated Austin and Brooklyn?) I imagine one thing working against larger metro areas—let’s add Portland and, to a lesser extent, Seattle to the mix as well—cultivating a distinguishing music style is the in-and-out migration of young creative types. A good portion of the artistic work comes from individuals with shorter roots to the region and a poorer sense of the city’s music history.

Minneapolis has a long history of well-loved, well-known, and well-remembered musicians and bands who’ve called the city home. Dylan, Prince, the Replacements, Hüsker Dü, yadda yadda—all regarded as seminal “Minneapolis artists.” But there’s nothing essentially “Minneapolis” about Robert Zimmerman’s raspy storytelling, the skeezy grooves of The Artist, or the charging punk of the ’80s. Nothing in the guitar chords, drum kicks, or synth riffs. Without outside knowledge of the band, it would be nearly impossible to pinpoint where the seminal bands came from. Maybe, if explicit enough or Google-able, you could guess from some revealing lyrics . . .

Two bands notorious for name-dropping their home state are the Hold Steady and Motion City Soundtrack. (For the latter, it’s even encoded in their name!) And neither of them, in my opinion, connects music to place in anything more than a superficial way. While mentioning Lyndale Avenue or City Center may serve an autobiographical or narrative end, the references are merely cultural touchpoints for the listener a character in the song. Depending on the track, artists like these come off as either encyclopedic city slickers or desperate crowd-pleasers.

So what about Duluth? The harbor city’s biggest cultural exports are, arguably, Low and Trampled by Turtles. But just like Prince and the Replacements, Low’s shoegazing alt-rock and Trampled by Turtles’ rootsy bacchanalia aren’t particularly “Duluthy.” A half-liquored-up music-theory graduate student might contrarily try to argue that the cold, foggy winters of Duluth lend a mellow, introspective quality to Low’s songwriting; or that big-small town vibe of downtown Duluth is the origin of the celebratory togetherness of Trampled’s folky bombast. I believe that music can capture the atmosphere of a place as large as a city, but I don’t think it can be accomplished through rock or pop.

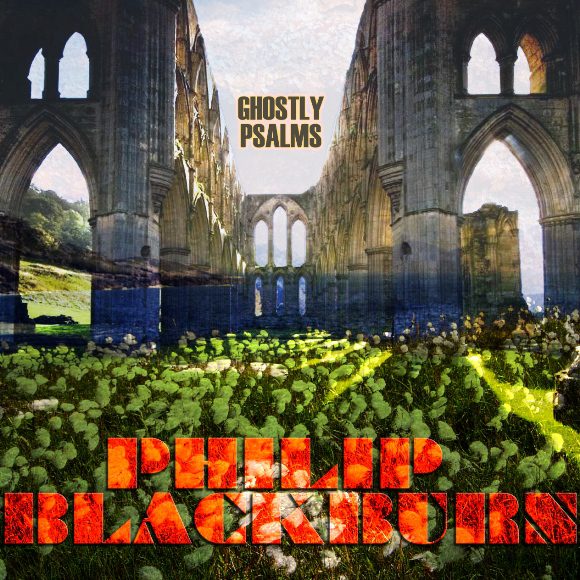

Not to sound like an old saw . . . but this is a perfect realm for experimentalism—like the combination of found-sound manipulation and abstract choral music of Philip Blackburn. Blackburn is a UK-born “environmental sound artist” who’s been doing much of the album production work for the fabulous and under-appreciated innova record label based in St. Paul. After about 20 years with innova, the label is releasing what amounts to Blackburn’s “debut album,” Ghostly Psalms (due out February 28). The lead-off track from the album is “Duluth Harbor Serenade,” an 8-minute wander along the shore of Lake Superior and the up the cobblestone avenues of the taconite city.

“Duluth Harbor Serenade” is a montage of found sounds mingled with immersive public performances in the city. (Watch the video below.) The shrill bellows of fog horns, piercing wail of ambulance sirens, and tolls of church bells comingle with the laughter of school children, buzzing chainsaws, an impromptu street-corner choral arrangement, lapping waves, and random loud instruments played and recorded simultaneously throughout the city. According to innova, the composition was “heard over several miles.”

Blackburn’s serenade is, I think, the perfect example of music capturing the “sound” of a city. Listening to it brings me back to day trips with my dad and brother to Canal Park and crooked evenings walking out of Fitger’s. The recording samples he chose to spotlight on the track speak to Duluth’s industrial past—the boats pushing through the harbor, the railcars loading and unloading ore from the Iron Range—in a very honest way. One example of someone trying this out in Minneapolis—to a much lesser extent—is Jeremy Messersmith at the end of his song “Light Rail.” These are the sounds that make the city what it is, turned into music. On top of that, by bringing the performance into the streets, Blackburn indirectly engaged Duluth’s whole population with his art.

I’d argue that a work like “Duluth Harbor Serenade” is possible for every city, every town. It’s up to the artist, of course, to single out the integral, nostalgic, idiosyncratic snippets of noise that make the place memorable, that turn a city into a hometown.

—Will Wlizlo

Profound post-script of the day: If you add some clever spacing and capitalization to the word “taconite,” it becomes “Taco Nite.” That is all.

I know I’m totally missing the point by commenting on your intro, but I think that the Twin Cities sound is totally a definable thing. There’s a bit of Midwest americana and North woods folk mixed in with a more urban punk and new wave style. In hip-hop we’re known introspective, socially conscious content and left-field production.

It’s a bit insulting referring to The Hold Steady and Motion City Soundtrack’s name-dropping as “superficial.” I find these hat tips to be driven by pride more than anything in their lyrics. Seeing MCS play to just a couple dozen people at the Foxfire to headlining and selling out the Mainroom should give them a pretty solid sense of hometown spirit, one that musicians most easily translate into song.

But Zach, what separates the urban punk, new wave, and even Midwest Americana written around Minneapolis from urban punk, new wave, and Midwest American written in Chicago or Milwaukee. And more importantly, how do those differences evoke a (for lack of better terminology) Minneapolis feeling? How do they convey the street life, the “placeness”? You bring up something I hadn’t thought of, though: politics. I’m not exactly sure how it would be done–perhaps dipping not only into the substance of political discourse of a place, but also that place’s political tradition, if you will. (The conscientious bipartisanship of the Arne Carlson years, maybe?) But that brings up the question (which I can’t answer) of how you convey the zeitgeist through an established genre.

Steve, I’d never argue that THS and MCS lack a pride of place. But I’m sticking my guns about the superficiality of the name-checking. For me–and to those band’s credits–the CC Club or Washington Avenue bridge are just landmarks embedded into more universal songs about relationship hardships and identity formation. Hypothetically . . . replace “Triple Rock Social Club” with “Bowery Ballroom” and you don’t get a song that sounds like New York . . . but you’ve still got a song about getting dumped and walking home in the snow without your jacket.

From my perspective, just as much as the background noise of a city (horns, traffic, voices, etc.) a city’s sound can be defined by the individual bands that lend their voices to that sound as a whole. So, nothing about the way bands play here instrumentally defines anything local (though Paul Metzger might get close to creating something unique enough). But overall, a guitar/drum/organ/etc. sounds the same here as it does anywhere. When I hear a band member’s unique voice though, and begin to associate that voice with this locality, I think that that voice becomes a piece in the overall local patchwork. So the overall “Minneapolis sound” I guess is (to me) defined only by the unique voices that make it up at any given time. And I guess these voices stature plays a certain part as well – i.e. P.O.S.’s voice is probably more evocative of Minneapolis’s sound than a lesser known local artist. Does that make sense? I think trying to find an overarching “sound” is erroneous, however it is possible to define any area’s sound by the unique identifiers in it, and since instrumentation is by nature not very unique, this falls to individual voices.

When it comes to instrumental music I guess we’ve got a whole new debate.

I guess I just hear a negative tone in the word “superficial,” when (despite some of the bleak undertones) a word like “non-essential” would be more appropriate. Nevertheless, hearing Craig Finn sing about walking across the “Grain Belt Bridge” rather than the Brooklyn Bridge is a pleasant wink to the fans who followed him in his early Lifter Puller days, and I like those warm fuzzies.

Glad you liked the Duluth aural experience. I have a ways to go before capturing the sonic essence of every city and town, but I did record/perform/publish “Habanera: A Sound Walk Through Old Havana, Cuba” which has plenty of uniquely-local flavor.